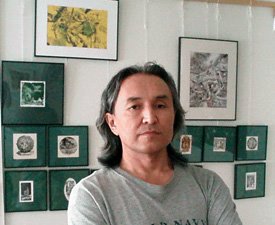

We are seated in Serik Kulmeshkenov’s studio in downtown Minneapolis. Kulmeshkhenov’s face is sober as he tries to explain his artistic approach to the precision etchings that embroider the walls around us. These are bold images, underwritten by a surrealist perspective and scored with lines so slender that the untrained eye has difficulty dissembling one from the whole.

We are seated in Serik Kulmeshkenov’s studio in downtown Minneapolis. Kulmeshkhenov’s face is sober as he tries to explain his artistic approach to the precision etchings that embroider the walls around us. These are bold images, underwritten by a surrealist perspective and scored with lines so slender that the untrained eye has difficulty dissembling one from the whole.As we page through the artwork in his portfolio, it is difficult to believe that the creator of hundreds of these delicately carved bookplates is legally blind. The ex libris are consumed with a density of detail and insight that point towards understanding the artist as a well-read, inquisitive man whose grasp of personal iconography rivals that of Sigmund Freud. They are also the works of a man who was forced to give up his extensive reading habits when, at twenty-seven, he lost a significant portion of his eyesight due to Behçet's Disease, a rare autoimmune disorder.

Language of Surrealism

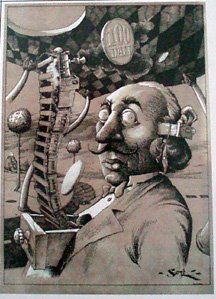

Despite (or perhaps because of) his visual difficulties, Kulmeshkenov's imagination seems continuous with the intellectual environment around him; his artwork draws from diverse themes in literature, medicine, mythology, political history, and even pop-culture. Some bookplates illustrate the legacies left by artists like Fyodor Doestoevsky, Vladmir Nabokov, Thelonius Monk, and Antoine de Saint Exupéry. Some of them are personal tributes to friends and colleagues. While he refrains from mining the artistic traditions of his native Kazakhstan, cultural symbols from across the world (especially Japan, he says) often appear in his etchings and cartoons to serve as landmarks in a complex landscape of associations.

"Sometimes I like lots of detail, can keep going and going and have to tell myself when to stop,” Kulmeshkenov reflects, “[Art] is not like science, like mathematics and physics, when things end as they should. Especially in surrealism. I like surrealism because of my problem with vision. It's difficult to look at landscape - I need to use the language of surrealism."

"Sometimes I like lots of detail, can keep going and going and have to tell myself when to stop,” Kulmeshkenov reflects, “[Art] is not like science, like mathematics and physics, when things end as they should. Especially in surrealism. I like surrealism because of my problem with vision. It's difficult to look at landscape - I need to use the language of surrealism."Kulmeshkenov’s “language of surrealism,” is a powerful mapping of the relationships between symbols and meanings both public and private. Clearly his push towards almost perpetual detail reveals a mind that sees beyond the traditional landscape and into the synaptic associations that bestow meaning upon it. It is indeed, a language with universal appeal.

It is no surprise, therefore, that Kulmeshkenov’s audience is truly international. His engravings, cartoons, and digital photography have won awards and honorable mention in over a dozen countries including Argentina, Iran, Korea, and Great Britain.

To Say the Maximum Using the Minimum

Despite his self-professed drive for detail when it comes to engravings, Kulmeshkenov also favors simplicity in art. Leaning back onto the cushion of his couch, he swipes his fingers through his hair and tells me that his favorite professional cartoonist is Gary Larson, known for his Far Side cartoons. Larson is spare in his use of language, Kulmeshkenov explains, “It’s like pantomime, like what Charlie Chaplin could do with movement…to say the maximum using the minimum.”

Photography – black and white photography especially – particularly lends itself to that goal of saying the maximum using the minimum. We look through a stack of photos on the table that seem to illustrate this. One features a grouping of variously sized bent nails in desolate surroundings. The effect is tragic. “This one is called Family of Nails Suffering in Desert,” he says, patting the surface in front of us, “I did that on this table. I got the idea one day and went and asked the caretaker here if he had any extra nails I could use. Large ones.”

Another photo reveals his humorous side – the reflection of a basketball hoop in a puddle with several crisp leaves floating on the surface. He turns the print around to reveal the story another angle tells – that of leaves captured in arching flight toward the hoop. “First Shot of Autumn, I call it,” he says, “Fifty percent of it is in the title sometimes.”

Kulmeshkenov’s cartoons and illustrations have also been popping up locally in The Rake. Bird Flu, a visual play on words, is a line drawing of a robotic bird looking almost quizzically at the wind-up mechanism planted into its back. Another drawing, which appeared in The Rake, celebrated the opening of The Human Body exhibit at The Science Museum, depicting Snoopy unzipping his robe of skin to reveal the musculoskeletal structure within. Woodstock lies on the ground before him, having fainted from the shock.

Image in Translation

Kulmeshkenov moved to Minnesota from his native Kazakhstan in August 2000, to seek treatment for Behçet's Disease, a disorder that can cause uveitis (eye inflammation) and lead to chronic vision problems. He was twenty-seven years old and working as an architect for the government when his eyesight started to give out. Although Soviet treatments helped to restore his eyesight temporarily, the condition worsened over time, causing permanent damage and costing him a career in architecture.

It was during his convalescent periods that Kulmeshkenov began to take an interest in engraving bookplates – he saw a newspaper article about the art and began to teach himself. Over time, he built up a network of mentors and ex libris enthusiasts with whom he was able to swap tips as well as collectibles. The precision drafting that he had learned in architectural school translated well into the art of engraving; the style in fact has become part of his artistic signature.

At forty-four years of age, Kulmeshkenov eventually received a visa, which allowed him to move to the United States and pursue treatment at Rochester’s Mayo Clinic. Although his vision cannot be restored, it is an improvement over the almost nearly complete level of blindness he was at when he arrived.

To compensate for his disability, Kulmeshkenov has learned to work with a special magnifying device that projects images onto a wide screen television. He is grateful, he tells me, for the help he gets from state assistance for the visually impaired. His contact there is also blind and has a good sense of what his needs are. After finding out that he had been trying to do his work at the Public Library (which offers special computers for the visually impaired), she helped him to find equipment that would not only compensate for his impairment, but also be more suited for working with visual projects and massive file sizes.

Seated at his drafting table, Kulmeshkenov demonstrates for me. He places a piece of paper onto a well-illuminated platform that is attached to a projector-like instrument. Dials allow him to control for light and level of magnification. By looking at the television screen to his right, he is able to see what his pen is doing on the page before him. It strikes me that he is like a surgeon who does pinhole surgeries by sending a camera in to see what he cannot. It is a displaced image; a sensation that is not disconnected from its image, but rather translated into image with the assistance of prosthetic technology.

It took some getting used to. Yet, when in a state of flow and working toward a deadline, Kulmeshkenov admits to sometimes forgetting the device is there at all. “If I’m doing an engraving,” he says, “and there are shavings on the surface that need to go, I sometimes forget and turn to the television screen to try to blow them off.”

Visit Serik Kulmeshkenov's Website

Some of Kulmeshkenov's artwork will be on display at Vision Loss Resources (Lyndale and Franklin, in Minneapolis) from July 1st to October 1st. Exhibition organized by Very Special Arts.

Photos by Valerie Borey

No comments:

Post a Comment